This is part two of a four-part series published in partnership with Scenic Hudson.org’s HV Viewfinder.

Sometimes we’re told change will take decades, even generations. Then world-shaking events like the COVID-19 pandemic show us it really can happen in a hurry. Such is the case with climate change—too often, we’ve been told that altering our approach to energy, agriculture, and everything else associated with making our world more sustainable will have to be incremental. Suddenly, this year we saw that rapid shifting really is possible when we all feel the global urgency.

And urgency is exactly what climate change calls for. As 2020 recedes in the rearview—a year that brought us a global health crisis, record wildfires and hurricanes, and a new understanding of the interlinked and systemic inequities in American society—we wanted to ask a diverse group of local environmental advocates what they envision in their areas over the next decade, and just as importantly, how we get there.

In the Hudson Valley as elsewhere, the movements toward inclusivity and justice are being led by young people and people of color. At The River, we pride ourselves on elevating their voices. For this digital feature, we have teamed up with Scenic Hudson.org’s HV Viewfinder. Scenic Hudson, too, sees this region’s powerful citizen-activists building community and strengthening resilience in the face of climate change.

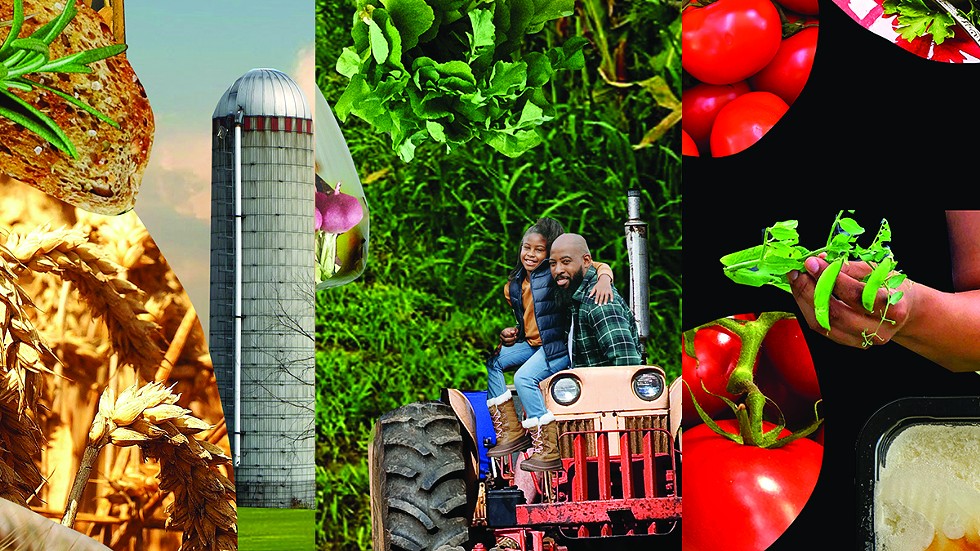

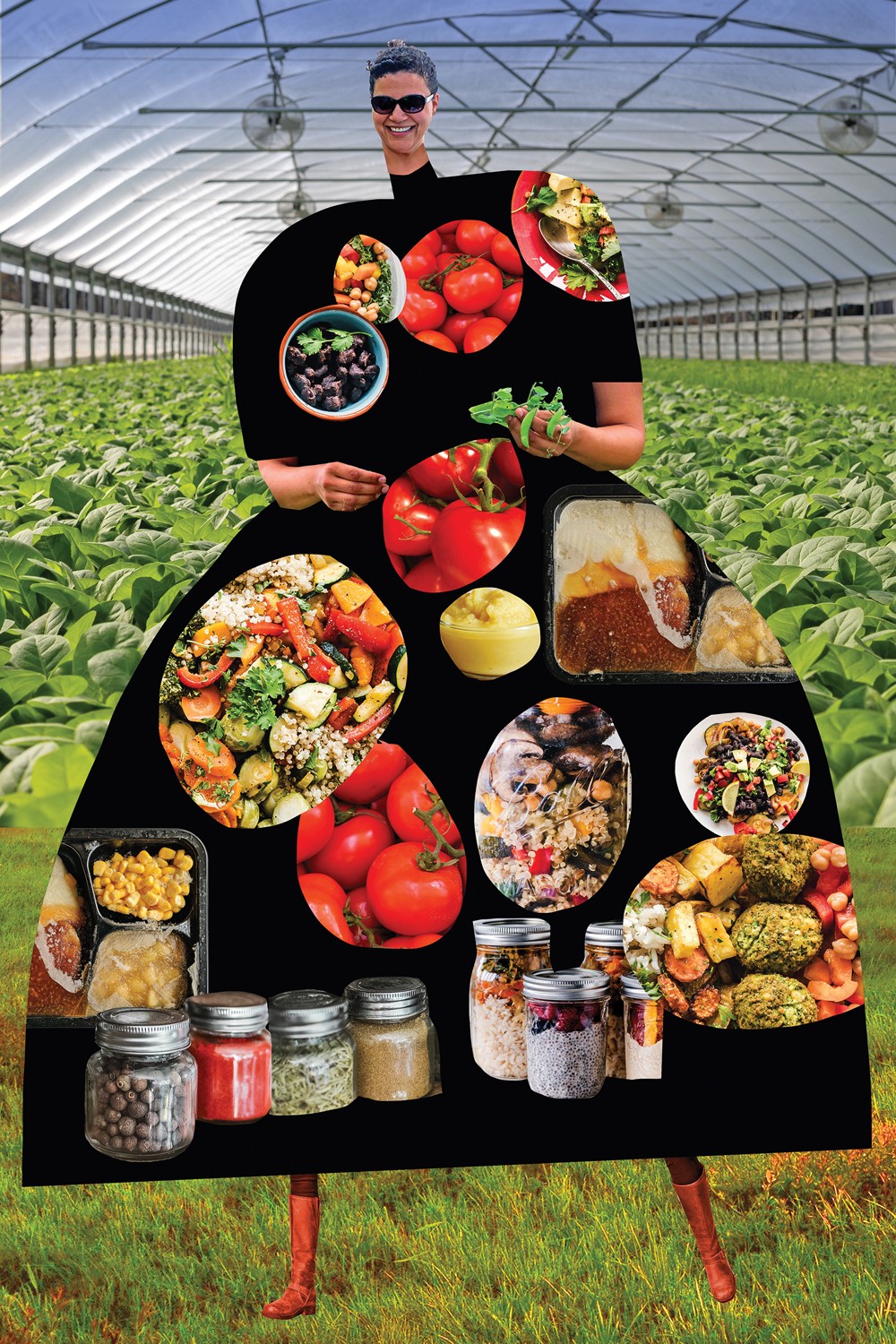

The series is enriched by collages depicting each subject and their vision, illustrated by the artist Johanna Goodman. Read on and dream what really is possible for the Hudson Valley—and within shorter order than we might think possible. — Lynn Freehill-Maye and Phillip Pantuso

Stiles Najac

Food Security Community Liaison, Orange County Cornell Cooperative Extension

Co-facilitator, Hudson Valley Food System Coalition

What I envision: A regional processing effort could create components for take-home frozen meals. In the greater Hudson Valley, we have 150,000 people who are food-insecure. Right now we have the GleanMobile, where we find excess food from local farms, harvest or repackage it, and distribute it to soup kitchens and food pantries. In Orange County we rescue an average of 200,000 pounds a year. With access to fresh fruit and vegetables, there are a lot of barriers. People are working two jobs and don’t have time to cook, or they’re unfamiliar with certain foods. And so we talk about how we break those down. Often the conversation has turned to processing food into actual meals. There are agencies doing it out there in other states, even in New York State. But we’ve never really looked at it from a regional perspective. There are food rescue agencies that do simple processing here—apples into applesauce, tomatoes into tomato sauce. Let’s take it a step further. What if, during the height of the season, we set aside some donated food for meal components? You could have a recipe like two zucchini packets, one corn packet, and you’ve created succotash. You could send a bunch of these to soup kitchens, or even to schools.

How we get there: There’s a working group of us talking about this. Even if we lean on volunteers to do all the processing, flash-freezing, labeling and creating recipes, we still need funding for a paid staffer. The interest is definitely there. There are community resources in each county—we might have the space, the volunteers, the food—we just need to coordinate everything. It’s really achievable 10 years out. It’ll be one step closer to people consuming fresh fruits and vegetables in ways they’re comfortable with.

Brooke Pickering-Cole

Executive Director, Hudson Valley Farm Hub

What I envision: A more resilient food system that includes reviving the growing of small grains in the Hudson Valley, which has been lost. We want to encourage infrastructure development so that wheat, for example, can be milled in the Hudson Valley, and farmers who want to grow these products have an outlet for them. Why can’t we see our kids in the local schools every day eating local bread? We’ve all become dependent on products that are traveling a great distance, and that has an environmental impact. To the extent we can produce food locally, we should—that is part of our obligation, and good for food security. It also gives regional farmers something else to produce on their farms. It would take a market, adding small grains in the rotation, and being part of the revival of a crop that can produce food for people locally.

How we get there: It would take infrastructure for grain-cleaning and milling, which might require philanthropy, government, and entrepreneurship—the classic public-private partnership. It’s challenging here—it’s a very wet climate for growing grains. So we would need more research on production practices, and variety trials happening on multiple farms. And also education, information-sharing, and technical support for the farmers—everybody working together.

Jalal Sabur

Cofounder, Sweet Freedom Farm

Cofounder, Wildseed Community Farm & Healing Garden

What I envision: Abolishing prisons and using land as an economic alternative. The Hudson Valley has 16 prisons, and most are on land that used to be a farm. How do we use those spaces for agriculture and get back to a Hudson Valley, not a prison valley that puts people in cages? Sweet Freedom is a worker-owned cooperative space that’s part of training the next generation. It’s kind of like a pancake or a breakfast farm, and we have a lot of events we call Abolition & Waffles. We serve maple syrup, apple syrup, wheat, sorghum, millet—all the things we have cultural references to—and connect that to the history of the abolition of slavery. During the abolition movement in New Lebanon, they would boycott sugar—which was produced with slave labor—and use maple syrup and apple syrup instead, supporting local products at the same time. When we’re doing it now, we’re talking about abolition and local jobs and economic alternatives. Abolishing prisons may seem far-fetched, but abolishing slavery seemed far-fetched, too. It’s something people worked at for hundreds of years.

How we get there: There’s a movement that needs to happen. We would try to secure more land and build agricultural infrastructure. We’d work with people interested in helping to develop more land-based projects that can be a space for restorative justice. It’s a longer process, with political power and community building around it.

Click here to read part one of this series, Housing & Transportation. The final two parts of this series will be published this week. This article was also published in the January 2021 issue of Chronogram.

Johanna Goodman is an internationally exhibited artist whose principal medium is collage. Based in New York, she studied at the Parsons School of Design and was awarded the 2017 New York State Council for the Arts fellowship in the printmaking/drawing/book arts category. Follow her on Instagram @johannagoodman or Facebook @johanna.goodman.3.