Ecco, February 2007, $23.95

In his book of essays, Other Traditions (2000), John Ashbery speculates that he had been given the Charles Eliot Norton chair at Harvard because people secretly hoped he would finally explain his poetry: “There seems to be a feeling in the academic world that there’s something interesting about my poetry, though little agreement as to its ultimate worth and considerable confusion about what, if anything, it means.”

Despite his reluctance to explicate his work, he does go on to say something about what poetry means to him: “For me, poetry has its beginnings and endings outside thought. Thought is certainly involved in the process. In fact, there are times when my work seems to me to be merely a recording of my thought processes without regard to what they are thinking about. If this is true, then I would also like to acknowledge my intention of somehow turning these processes into poetic objects.”

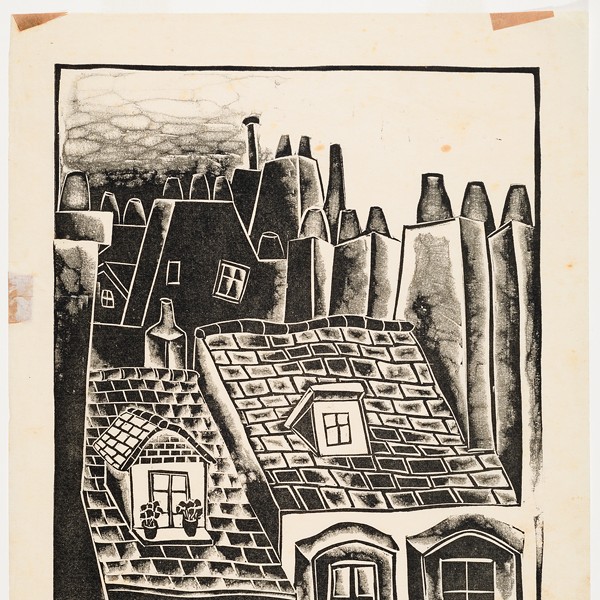

Note that it is not Ashbery, but the processes that are doing the thinking. The poems in his 26th collection, A Worldly Country, are dazzling thinking machines. Deeply attentive to sound, the poems are playfully formal (the title poem rhymes “hovel” with “novel”; “Tweety Bird” with “occurred”). If they were music, they’d be jazz—improvisational, witty, whimsical, and uniquely American.

Like many of his compatriots from the New York School, Ashbery’s poems are more concerned with tone than they are with subject, but the shifty nature of both forms a kind of theme. And like the country we live in, the poems in this collection are constantly reinventing themselves. Ashbery’s mind is manic the way cities are: flashing with slogans, full of crushed dreams and the unlikely beauty found in visual irony. If you’ve ever watched a baby’s face for any period of time, you know how quickly human mood can shift when not filtered through the self-consciousness of identity. The poems in this beguiling collection, while formal and full of urban sophistication, capture that lack of attachment. This prism of moodiness is evident in poems like “America the Lovely”:

If it’s loveliness you want, here, take some,

hissed the black fairy. Waiting for the string quartet,

on the corner, denatured I wondered what the heck.

I’ll have some too. They call it architecture,

I was told. Anything to sift the discerning

from the mob-capped mob, their stiffened fright wigs

marching against the breeze improbably back

into colonial dreams and days.

While John Ashbery does not write about John Ashbery, the poet’s voice streams out radio waves like those of Cocteau’s Orphee, or like hisses out of angry nymphs and fairies, and, in the process, his ars poetica is revealed. Do not confuse detachment from self with lack of feeling; the poems are full of bitterness and loveliness and elation and he generously encourages us to take what we need. The only thing he won’t do is tell us how or when to feel. His poems teach us about the flimsiness of the ego’s need to attach to feeling and encapsulate experience in stories. Just when you think you’re following a thread, Ashbery exercises the verbal equivalent of a shrug or a tip of the hat, and leaves. He ends one stanza in “And Other Stories” with “The clock was on the verge of striking. And you know something?/ It never did! Not while I was there anyway.”

Ashbery is currently Charles P. Stevenson, Jr. Professor of Languages at Bard College. The academic world may go on looking for the key to understanding his poems, but, if we’re lucky, he’ll continue to take pleasure in evading it. Despite his resistance to narrative, the multifarious voices in the poems are gentle and patient with those of us who falter a few steps behind. He opens “Asides on the Theorbo” with “It’s OK they said, it’s all right not to know/ where any of this is coming from. Trust your judgment.” Assuaged, the reader can keep driving through A Worldly Country with the radio on search, picking up multiple frequencies to form what could actually be a truer story: fragmented, omniscient, and deeply evocative.

—Caitlin McDonnell