Clear yam noodles, Korean veggie pancake, string bean, pork chop, turnips, tofu with mushroom and carrots, and rice at Seoul Kitchen.

A culinary triumph is often something sublime; an epic culinary failing can, if nothing else, turn into a pretty fascinating car-wreck spectacle. But mediocrity really pisses me off—and there’s a lot of it out there.

It can take a truly Herculean effort not to lose it in the face of all the middling non-entities preparing food or, at least, to keep from a slide into despair.

There are certain cuisine types that fall victim to this more often than others. It’s a tough slog to find those places making really transcendent Mexican food, or pizza that makes you want to lift your fists heavenwards.

And the spectrum of many Asian restaurants out there isn’t any less baleful.

From where I’m perched in Saugerties, my trusty GPS tells me that within a 12-mile radius, there are more than 25 Asian restaurants, most of them offering Hunan-style or Sichuan-style Chinese food. I’ve tried a clutch of them and have this to report: with the notable exception of the Little Bear Café in Bearsville, the scallion pancakes and mu shu pork are as indistinguishable as the ubiquitous menus printed in that vaguely psychedelic red and green ink. After eating at any one of them, with your belly resignedly full and your soul plagued by a faint haunting of guilt for the fat, oil, and sodium you’ve crammed into your mouth, you still know you’ll keep trying other similar restaurants out because you keep waiting to find the one that lives up to the promise inherent in many Asian cuisines: balanced contrasts, ingredients that exist independently and in synchronicity, and bright, clean flavors.

So when an Asian restaurant does shake higher on the Richter scale than its many peers—and I’m gratified to be writing about two of them: Yum Yum Noodle Bar in Woodstock and Seoul Kitchen in Beacon—it’s worth asking why.

Most people will tell you it’s strictly a matter of authenticity. The closer a dish is in flavor, composition, and texture, to something served in the mother country, the more vastly superior that dish’s very existence. I personally find that whole notion faintly ridiculous. If mu shu pork as we know it isn’t a dish someone from one of China’s provinces might recognize, isn’t it still an “authentic” expression of what occurred with Chinese cooking when it arrived on American shores? Maybe no one south of the Rio Grande ever eats chimichangas, but to me it’s a fine example of Mexico and Texas shaking hands.

What really makes a restaurant stick out is a matter of execution—putting a serious effort into its food’s preparation—and a unique vision. Maybe the cuisine is truly “authentic” or maybe not; that isn’t what matters.

Yum Yum Noodle Bar

The Yum Yum Noodle Bar, less than a year old and set in the dead center of Woodstock, is a pan-Asian affair open solely for dinner. Owned and run by Erika Mahlkuch, formerly of Saboroso restaurant in Rhinebeck, and Nina Moeys-Paturel and Pierre-Luc Moeys, owners of nearby Oriole 9, it makes gestures to Japan, Thailand, Vietnam, China, and Korea. Looking at the menu on their website a few days before I drove over, I’ve got to cop to a little bit of prejudice: the menu offers up bibimbap, construct-your-own noodle bowls, peanut noodles, beef salad—a grouping that really covers all the bases. I got the same sort of feeling that settles over me when I see Thai restaurants that also offer sushi, a feeling that makes me want to ask, “Isn’t just one hard enough?” But following that line of reasoning starts to bring you back towards notions of “authenticity” and I was willing to give Yum Yum a fair shake and just go with it.

But still, I wanted to know, so before I ate, I asked Mahlkuch, “Do you think all these cuisines have something in common?”

After a long pause, she said, “No. They all have a different style. The Japanese is more delicate. Not spicy. More delicate flavors. With Thai you have hot, salty, sour, sweet. There’s the Asian of Thai and Vietnamese, and those flavors are kind of similar. The lime and the lemongrass and the chilis.”

“What’s the appeal of this sort of cooking for you?”

“The ingredients—being able to work with something different. If you’ve been cooking for a while, you’ve probably done a lot of French or Italian, and to be able to go beyond that into another kind of cooking that people aren’t as familiar with is fun and fascinating for us.”

“And what about the concept of the restaurant at its inception?”

“We brainstormed about what the area needed and we listened to the people. People would say, ‘What about a noodle bar?’ And it made sense. We’ve all been to noodle bars in the city, and Luc [Moeys] traveled in Japan, so we brought everything back here. We wanted something that was healthy, clean, and affordable for everyday dining. And, so far, it has done very well.”

Mahlkuch mentioned that Momofuku in New York City had provided a healthy dose of inspiration for Yum Yum, something that made sense when we sat down and ordered. The flavors of Vietnam or Japan are there, or sometimes just the flavor of an idealized Asian dish—but these are non-traditional-dish-specific, working with the same panoply of tastes, if not the exact compositions. But it wasn’t conceptual; nothing broken down, deconstructed, atomized, or otherwise deliberately rent asunder. It seemed more like the owners’ mix tape of favorites and covers.

And as for execution, Yum Yum acquitted itself well: the vegetable dumplings were crisp and earthy, without a heavy sheen of oil all over the skin; the seared calamari in a mild chili sauce was genuinely perfectly cooked; the pork buns—a direct lift from Momofuku—had all the flavor of their forebears, even if the texture wasn’t quite as silken. We didn’t walk out without some criticisms, though: while the crispy pork in my noodle bowl was terrific, as was the chicken in my wife’s pho, and while the vegetables in each bowl were beautifully cooked, the broth itself was really underseasoned, and there’s only so much soy sauce you want to pour into your entrée. This is a pretty easy fix, though. And the Thai iced coffee was poor—plain coffee, kind of weak, with what tasted like evaporated milk rather than condensed, and none of the thick, intense bitterness and intense sweetness you get from the best examples of the genre.

Yum Yum is slated to open a second location in late February at 275 Fair Street in Uptown Kingston, which will be open for lunch and dinner. Moeys says that plans are also in the works for launching Yum Yum catering and food truck lines.

Seoul Kitchen

Over in Beacon, at the far end of Main Street, almost out of town, sits Seoul Kitchen, owned and operated by Heewon Marsharo. Marsharo, born in Seoul, was once an actress in Korea before moving to Japan to get married and sell life insurance. She was, she informs me, the number one salesperson in her company. When her marriage ended, she lit out for the United States. Marsharo says she didn’t know a single person in America, but thought she might learn something about herself through the adventure.

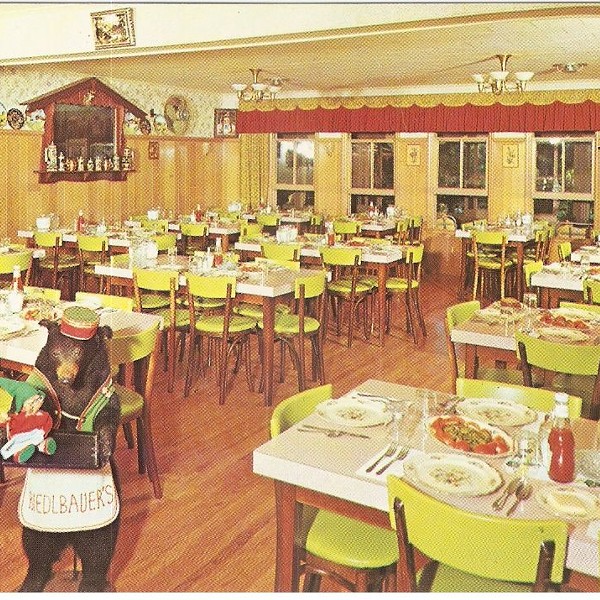

Seoul Kitchen really isn’t a restaurant, per se. Marsharo describes it as a Korean deli, but this is accurate only in the most minimal sense. There is a cooler selling sodas, drinks, and a few packaged foods (in addition to Korean dried anchovies—the best available, says Marsharo), and there’s a tiny steam table with dishes Marsharo prepares in an absurdly small kitchen space at the back of the room. Nothing, really, like the densely stocked shelves, sprawling steam tables full of just about every food imaginable, and the blinding fluorescence of Korean delis all over New York City.

That tiny steam table is the main attraction for the approximately 25 or so customers who come in every day to buy their lunch of traditional Korean dishes by the pound, or entrees like bibimbap at night. Many customers come in multiple times weekly.

I went into Seoul Kitchen at around 3 p.m., after the lunch rush. Marsharo leaned her head out from the kitchen and asked, “Chronogram? Yes? Are you hungry?”

Marsharo just seems to understand she’s a good cook, grateful for the praise I offer the sweet potato noodles, marinated chicken, kimchee, a vegetable pancake, and a cup of fermented bean paste soup, but not all that surprised. The meal tastes like something prepared by the Korean grandmother of my imagination. If you were inclined to think in terms of “authenticity,” this would probably be it, but that isn’t paramount to Marsharo’s mission, either. Really, this all started by default. She couldn’t get a job in the insurance business like she’d hoped, and after she married her current husband, whom she met on a Metro-North train, her cooking vocation began to make itself manifest.

“Each time I cooked, my husband said, ‘Delicious! Delicious!’ and he’s American, right? So we started to invite people around. And they said it was delicious. And I liked that. And I liked to cook. I’ve been cooking for myself for 30 years. Even if I was very busy. I like my food. I don’t like the food in restaurants. Sometimes its good, but I like my food. But I didn’t want to work as a waitress or cashier. So, okay, what about having American people know about Korean homemade food? It took almost three years, then I found this place.”

Marsharo and her husband built Seoul Kitchen up from scratch, installing all the hardware and giving the space a quiet, decorative touch. She focuses intently on her cooking, and also keeps her eyes cast off beyond the room’s walls. She describes another project she’d like to undertake someday soon, a restaurant offering her dishes where all the diners sit at one big table eating and communing. Other than that description, she doesn’t elaborate. “I have to build my dream. I concentrate every day on my dream. I just started the beginning of my dream now. But I have to continue. Like first level, then second level, maybe third level.”

I ask what the third level would be. “No! I don’t even think about the third,” says Marsharo. “Because I’m still at one. I have to concentrate on one, then think about two. I’m building my dream,” she says and gestures at the room. “This is my American dream.”

Yum Yum Noodle Bar Yumyumnoodlebar.com

Seoul Kitchen (845) 765-8596